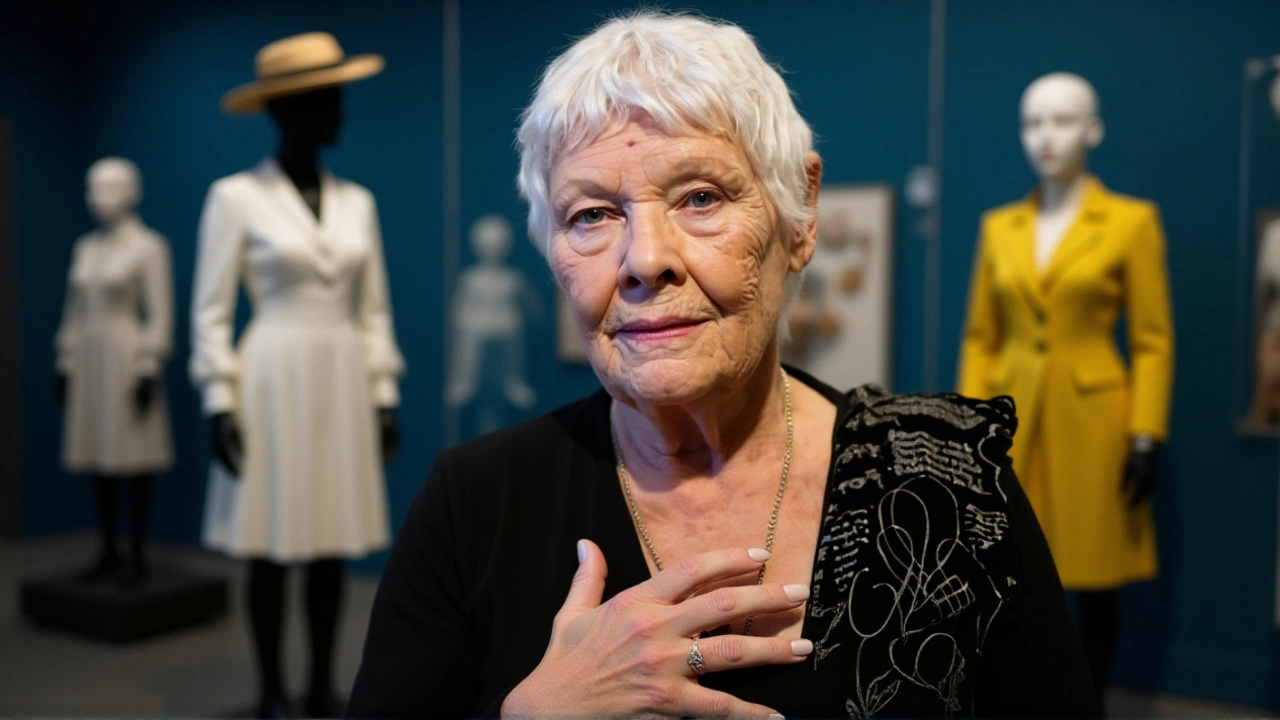

When Dame Judi Dench stepped into the Fashion and Textile Museum on September 26, 2025, she didn’t just open an exhibition—she unlocked a vault of cinematic magic. The Oscar-winning actress, whose own performances have been shaped by fabric and thread, penned the foreword to The Costume House: The Inside Story of Cosprop, the companion book to Costume Couture: Sixty Years of Cosprop83 Bermondsey Street, London SE1 3XF. It’s not just a display of gowns and hats. It’s a masterclass in how costume transforms actors into legends.

The Magic Behind the Fabric

Cosprop, the legendary London-based costume house founded in 1965 by John Bright OBE, has quietly dressed the faces of cinema for six decades. Think Colin Firth’s Mr. Darcy waistcoat, Maggie Smith’s Downton Abbey emerald gown, Helena Bonham Carter’s 1908 lavender silk dress from A Room with a View, and Cate Blanchett’s velvet-and-gold Elizabethan robes. These aren’t replicas. They’re originals—worn, stitched, dyed, and distressed by hand in Cosprop’s cluttered, aromatic workshops beneath London’s railway arches.

“Actors walk in with just a script and the name of their character,” Dench wrote in her foreword. “They walk out with that character fully formed in their mind, having brought him or her to life through the angle of a hat, the fabric of a coat or the feel of a pair of shoes.” That’s the alchemy Cosprop specializes in. A single lace trim can whisper nobility. A frayed cuff can scream poverty. A jacket rewaxed in a huge vat? That’s how Jack Sparrow got his sea-salt soul.

From Script to Screen: The Craft

The exhibition doesn’t just show the costumes—it reveals the sweat behind them. Mood boards pinned with torn fabric swatches. Sketches in pencil and ink, annotated with notes like “too stiff” or “needs more decay.” Swatch books labeled “1890s Mourning Wool – 3% Lichen Dye.” You’ll see how a silk gown for The Duchess was hand-painted to mimic age, how Lesley Manville’s 1950s Parisian skirt was deliberately frayed at the hem to suggest years of walking the Champs-Élysées.

John Bright once explained that every costume for Maggie Smith had to “have an edge.” Her green Downton ensemble? A high-necked blouse densely beaded with gold thread, paired with a gown that shimmered like armor. “She’s not just a lady,” Bright said. “She’s a force. The costume had to match that.”

Even the accessories tell stories. Boxes labeled “narrow braces,” “hessian aprons,” and “spats” line the walls. One shelf holds rainbow-hued lace—each strand hand-dyed, each pattern traced from museum archives. Cosprop doesn’t buy costumes. It builds them, stitch by stitch, from historical blueprints and sheer intuition.

A Legacy Shared: V&A and Beyond

The connection between Cosprop and the Victoria and Albert Museum runs deep. On November 4, 2025, Dench returned to the V&A to unveil a permanent display of A Room with a View costumes bequeathed by Bright himself. Alongside actor Rupert Graves, she stood before the lavender gown that once draped Bonham Carter’s Lucy Honeychurch—a garment now preserved for future generations.

This isn’t an isolated moment. Cosprop’s archive is one of the most comprehensive private collections of 20th-century costume design in the UK. And now, for the first time, the public can see how Emma’s Regency dresses were hand-embroidered, how Little Women’s 1860s pinafores were distress-washed to look lived-in, how The Danish Girl’s 1920s tailored suits were cut to subtly distort the body—mirroring the protagonist’s internal struggle.

Why This Matters

Costume design is often invisible. We notice the actor, not the coat. But Cosprop reminds us: character lives in cloth. The exhibition arrives at a time when streaming platforms churn out historical dramas faster than they can research them. Here, authenticity isn’t a buzzword—it’s a craft honed over 60 years.

Curated by Keith Lodwick, former V&A film curator and author of the exhibition’s companion book, and overseen by Dennis Nothdruft, Head of Exhibitions at the Fashion and Textile Museum since 2003, the show is as scholarly as it is sensual. A curator talk on October 12, 2025, will reveal how the team selected pieces from over 150,000 items in the archive.

It’s no coincidence this exhibition opens alongside the David Bowie Centre at V&A East and the Marie Antoinette Style show at the V&A. London’s autumn 2025 is a festival of sartorial storytelling—and Cosprop is its quiet, brilliant heart.

What’s Next for Cosprop?

With the exhibition running until March 8, 2026, the team is already planning a digital archive project. “We’re scanning every sketch, every dye recipe,” Lodwick told us. “The goal? To make this knowledge accessible to students, designers, and historians worldwide.”

John Bright, now in his late 80s, still visits the workshop once a week. “I don’t do much anymore,” he says with a chuckle. “But I still know which velvet needs to be washed in vinegar.”

Frequently Asked Questions

How did Cosprop become so central to British film history?

Founded in 1965 by John Bright OBE, Cosprop began as a small workshop supplying period costumes for BBC dramas. Its reputation grew after dressing Meryl Streep in Out of Africa (1985), where authenticity was critical. Over time, filmmakers realized Cosprop’s archive—featuring over 150,000 garments and accessories—could replicate historical accuracy better than any modern manufacturer. Its dye room, where fabrics are hand-treated with lichen, tea, and vinegar, became legendary.

Why is Dame Judi Dench’s involvement significant?

Dench has worn Cosprop costumes in over a dozen films, including Shakespeare in Love and Philomena. Her foreword isn’t just a celebrity endorsement—it’s an insider’s tribute. She understands how a hat’s tilt or a glove’s stiffness can unlock a character. Her public support elevates costume design from craft to art, helping secure funding and academic interest for future preservation efforts.

What makes Cosprop’s techniques different from modern costume production?

Most studios now use mass-produced rentals or digital printing. Cosprop builds everything from scratch using 19th-century methods: hand-dyeing with natural pigments, distressing with sandpaper and tea stains, and hand-stitching seams to mimic period wear. For Mr. Darcy’s coat, they used wool from the same Yorkshire mill that supplied 1813 tailors. This level of detail takes weeks—not hours—and is why directors keep returning.

Can visitors see the actual dyeing process during the exhibition?

While the dye room itself is off-limits for safety and preservation, the exhibition includes a full-scale replica of the workshop, complete with simmering vats, dyed fabric samples, and video loops of artisans at work. You can touch swatches treated with lichen dye, compare original and distressed fabrics side-by-side, and even smell the vinegar used to age silk. It’s sensory storytelling at its finest.

What’s the most surprising item on display?

A pair of 1920s silk slippers worn by Madonna in Evita (1996), each heel hand-carved from cork and painted with gold leaf. They were originally designed to look worn—but Cosprop’s team added micro-tears and scuff marks using a tiny brush and ground-up charcoal. The shoes are so fragile they’re displayed under inert gas. Few know they’re still wearable—just not walkable.

Will the exhibition travel after March 2026?

There are no confirmed plans yet, but the Fashion and Textile Museum has already received inquiries from the Met Costume Institute in New York and the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. A scaled-down version may tour regional UK museums in 2027, focusing on regional costume history and local film production. The full archive, however, will remain in London.